Plant innate immunity system

It is well known that the plant relies on an interconnected two-layered innate immunity system to protect the plant from pathogens.

The first layer - PTI

The first layer is the pathogen-/microbe-associated molecular pattern (PAMPs/MAMPs) triggered immunity (PTI) via cell surface-localized pattern receptors (PRRs), which can provide basal protection during the early pathogen infection (Boller and He 2009; Zipfel 2014). However, many eukaryotic biotrophic pathogens, including P. brassicae can hijack PTI by secreting effector proteins (Iswanto et al. 2022), and disrupt the function of host receptors to manipulate the innate plant immune responses. An example of that is how the clubroot pathogen can deploy chitin-binding effectors (PbChi2 and PbChi4) to suppress chitin-triggered immunity and escape plant surveillance, which was identified by Muirhead and Pérez-López (2022). Other mechanisms used by P. brassicae to establish the disease are the suppression of salicylic acid (SA) - mediated immunity using a secreted methyltransferase (PbBSMT) (Ludwig-Müller et al. 2015), the inhibition of SNF1-related kinase 1.1 (SnRK1.1) by the RxLR effector PBZF1, which increases susceptibility to the c lubroot pathogen (Chen et al. 2021a), and the inhibition of xylem cruciferous papain-like cysteine proteases (PLCPs) by the cysteine protease inhibitor SSPbP53 (Pérez-López et al. 2021).

The second layer - ETI

The second layer of plant immunity is named effector-triggered immunity (ETI), for which intracellular nucleotide-binding (NB) leucine-rich repeat (LRR, NLR) receptors are crucial for plants to detect pathogen effectors and mount a robust immune response (Jones and Dangl 2006; Li et al. 2015). The plant responds to pathogen effectors specially with NLR protein receptors and active hypersensitive response to prohibit the pathogen spread (Figure 1). Although the two classes of immune receptors involve different activation mechanisms and appear to require different early signaling components, a “zig-zag” model shows the importance of understanding the crosstalk between PTI and ETI (Jones and Dangl 2006; Ngou et al. 2022).

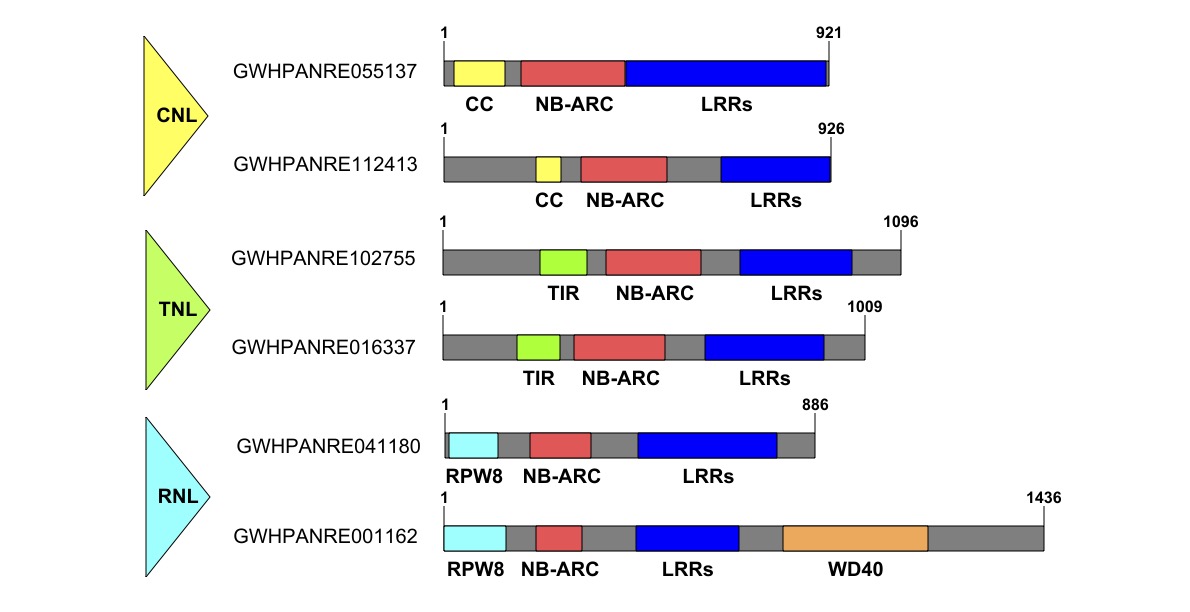

Generally, plant NLRs carry NB ATPase (NB-ARC) domain in the central and LRR domains in the C-terminal site. Functionally, there are two types of NLRs include sensor NLRs and helper NLRs. Sensor NLRs can directly recognize pathogen effectors to initiate effector-triggered immunity (Liu and Wan 2022). NLRs could be divided into three classes according to their N-terminal domains: coiled-coil (CC) NLRs (CNL), Toll/Interleukin-1 receptor/Resistance (TIR) protein NLR (TIL) and RESISTANCE TO POWDERY MILDEW 8 (RPW8)-like CC domain (RPW8) NLRs (RNL) (Barragan and Weigel 2021; Ngou et al. 2022). The CC, TIR and RPW8 domains function as signaling domains to downstream responses upon NLR activation. Plant sensor NLRs recognize pathogen effectors by direct interaction or perceiving the modifications of effectors. Then, sensor NLRs require helper NLRs to transduce immune signals (Jubic et al. 2019). An additional domain “integrated decoy” (ID) was found in some sensor NLR partners for direct effector interaction, while other NLR functions as an executor for immune signaling (Baggs et al. 2017; Newman et al. 2019).

NLR genes are key players in clubroot resistance. The availability of the whole sequenced B. rapa (AA genome), B. oleracea (CC genome) and B. napus (AACC genome) genomes provides ideal resources to investigate and annotate novel NLR gene family members (Chalhoub et al. 2014; Liu et al. 2014; Wang et al. 2011). The NLR is the largest group of R proteins in plants. It is reported that there are 641 NLR genes in B. napus, 249 in B. rapa, and 443 in B. oleracea (Alamery et al. 2018). Due to the lack of CR genes in B. napus (canola) germplasm, the canola progenitor B.rapa (Chinese cabbage) is considered a major source in CR breeding (Huang et al. 2017). Several candidate CR genes have been identified to encode NLR proteins in B. rapa (Hatakeyama et al. 2017; Hatakeyama et al. 2022; Matsumoto et al. 2012; Ueno et al. 2012; Wang et al. 2022; Yang et al. 2022; Zhang et al. 2021b) . For instance, CRa and Crr1a conferring CR in Chinese cabbage of B. rapa were successfully isolated and, and both encode NLR proteins (Hatakeyama et al. 2013; Ueno et al. 2012). Recently, Yang et al. (2022) identified two NLR genes from B. rapa (ECD-04), CRA3.7.1 and CRA8.2.4, through the transformation of B. napus. NLR genes have high intraspecific diversity and evolve rapidly. However, there is still a limited understating of NLR-mediated CR in the Brassica family. Individual R genes have been overcome by P. brassicae evaluation, and durable resistance remains elusive. Therefore, it is essential to discover novel NLR genes and to make them available for breeding purposes.

NLR genetic and functional diversity is crucial for plants to withstand pathogen evaluation. It is well known that NLRs have conserved and evolving members. So, genome-wide identification of the NLR family allows us to facilitate disease resistance genes exploration. For instance, Van de Weyer et al. (2019) presented the pan-NLRone in Arabidopsis thaliana by analyzing 64 accessions. Recently, The Solanum americanum pan-NLRome was defined and showed great potential in potato late blight resistance (Lin et al. 2022). However, knowledge of the NLRome in canola is largely unknown, and a complete picture of the NLRs in canola may therefore enable the identification of new CR genes.

The resistance mechanisms of all forms of clubroot-resistant germplasm available from seed companies are thought to involve the NLR protein family. However, traditional mapping and cloning methods require numerous generations to achieve. Although these commercial lines contain harbour NLR genes, the complexity of the canola genome and NLR genetic recombination trait prohibit using existing methods to clone them.